I don’t normally take binoculars with me when I walk out to get the morning newspaper—but maybe I should.

Summer is dwindling away, with the sun rising in the east farther and farther south. It’s been up for about an hour and half this Tuesday morning, and the light slants in across my left shoulder and under the bill of my ball cap. I’m glad to see the sun after so many clouds these last few days and nights as the remnants of Hurricane Florence drifted west into the Ohio River Valley.

The autumnal equinox is fast approaching and set to occur on Saturday. My farm is right in the middle of the continent about fifteen miles south of the Ohio River on the outskirts of Louisville in eastern Jefferson County, Kentucky. During migration this region of North America from Canada then across the Great Lakes and down to the Gulf of Mexico is known as the Mississippi Flyway—and millions and millions of birds are already on the move.

Here at home, my local year-round, resident birds are noisily active today—Northern Cardinals, Blue Jays, a Carolina Wren, a pair of Tufted Titmice, all twittering and flitting about in short flights among the trees and over the old hayfields. At summer’s end southbound warblers and vireos and other small birds who fly by night settle down in the thickets along my little stream and over at the pond for breakfast and a much-needed nap during the day. My locals are making it clear to these early visitors that these habitats are already claimed, and they should move on as quickly as possible.

As for me, I’m in no hurry. Ambling along my gravel driveway, strolling out to the newspaper box at the edge of the paved road, I listen to the birds’ chatter and begin thinking about what I might do after breakfast. Maybe I’ll take the morning off to study the trees and fields for migrants.

Suddenly, I catch a flash of white, something very white and high in the sky to my right over the south hayfield. What was that?

I stop and turn to focus my unaided vision on the shapes of the brilliant, gleaming white bodies and wings of two birds flying south, the white such a contrast to the blue sky. Huge white birds. Really big, and somewhat chunky—far too big to be local summer birds, such as Great Egrets, which do fish along the river and turn up by the creeks in area parks.

Not only are the two birds I’m watching too big, they are not slim and graceful, and I do not see long legs trailing behind. Their wings are not thin, but rather wide —and they are not completely white. The outer edges of their wings feature pitch black feathers, quite a contrast to the white ones.

White with black, white with black—I repeat this combination to myself, making mental notes about what I’m looking at. There are a great many birds with that contrasting feather pattern, birds I know from Florida and all along the the Gulf Coast in Texas. In a flash I run through the list, an ibis, a stork, even a goose. But the birds I can think of instantly are not big enough or the right shape.

Without taking my eyes off the birds flying powerfully and silently toward the south I fumble in my pocket for my cell phone. I know I’m going to have to rely on my overall mental impression of key details—they’re moving ahead quite rapidly—but maybe I can get a digital image or two.

A quick glance down to move my fingers across the phone’s screen, then point it up toward the sky and hope for something as I click. Two images—and the birds are gone!

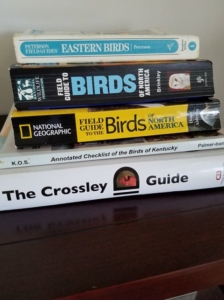

Walking on to pick up the newspaper, then back to the house, my mind keeps going over and over what I saw. All through breakfast in the kitchen I keep reviewing my impressions of the birds. Finally, I jot down a few handwritten notes, then pull out two field guides from the tote bag on the dining room table where I keep my binoculars. One has paintings, the other photographs, a pairing that is quite useful in the field. But I’m indoors with a memory, nothing to look up at to check details.

Hmm…I think I know what I saw, but before I look at the photos on my phone I want to check some other reference books. For the next fifteen minutes I look at more paintings and drawings and photos. Yes, yes, that seems a lot like what I watched—but in many of the books the bird in the picture is facing bill to the right, and the birds I watched were flying south and away from me, with their bills to the left. So mentally I have to rotate and reverse the images in the field guides. Is that like what I remember?

Yes, I’m becoming more and more convinced that I can identifying the birds correctly.

The clincher will be the photos. Or maybe not. They are really terrible. Oh, sure, the trees below and the little clouds above are crisp and clear, but the blue sky section in the center of the photo where the birds were flying is nothing but blue—where are the birds? I zoom in and zoom in some more on the area where the birds should be until I find two blobs of mostly white with black splotches, all heavily pixilated, and prepare to study. Not much to go on, but it is all I have.

As I look at the photos I need to think about the range and migration patterns of the bird species I have in mind. And I need to remember that what individual birds do during each season and on a particular day is heavily influenced by immediate weather conditions.

I study some maps, but as I do I must keep in mind that a map only summarizes historical data and observations. Many of the books in my library were published long before the days of citizen science projects and electronic data collection methods such as eBird. But even fifteen years ago, Kentucky ornithologists were noting an increase in observations of the species I’m investigating today.

I have one more option—consult reliable internet sources for more up-to-date information. Both the Cornell and Audubon websites provide more details about contemporary migration patterns, and more photos to study.

I am now confident that the answer to my question, “What was that?” is something I never expected—American White Pelican!

I know this bird from Florida and the Texas Gulf Coast, and something about their flight did make me think fleetingly of warmer days watching birds down south. If I saw them floating on the Ohio River I would have no trouble identifying their blocky shape.

But to see them flying over my farm is quite a surprise, something I never expected. This species, Pelecanus erythrorhynchos, is well-known to fly down from the Great Lakes to congregate on the lakes near the Kentucky-Tennessee border, often spending the winter over there. However, their usual route through the Mississippi Flyway to that destination is more westerly. Other pelicans heading all the way to Florida often take a more easterly route, over into the Virginias and Carolinas, but a high pressure system smashed up against the remnants of Hurricane Florence along the Appalachian Mountains may have forced them to alter their route slightly. While uncommon, seeing these two birds here is certainly within the boundaries of known flight paths.

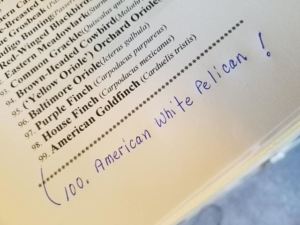

When I pull out the binder with my “yard list” for the bird species I’ve recorded during twenty-two years of observations here, I get another surprise. I discover that American White Pelican is species number one hundred! I’ve solved a puzzle—and achieved a new milestone.

And right now I’m going to put my binoculars next to my ball cap so I’ll be ready for more early morning birding at home tomorrow.

–Nancy Grant

Author…

Binge Birding: Twenty Days with Binoculars

To find out more about Nancy’s book, Binge Birding: Twenty Days with Binoculars